the truth about the reliant robin

Riding a tricycle can be so much fun.

By: Terry Burgess Sun, 31 Jan 2021

Features

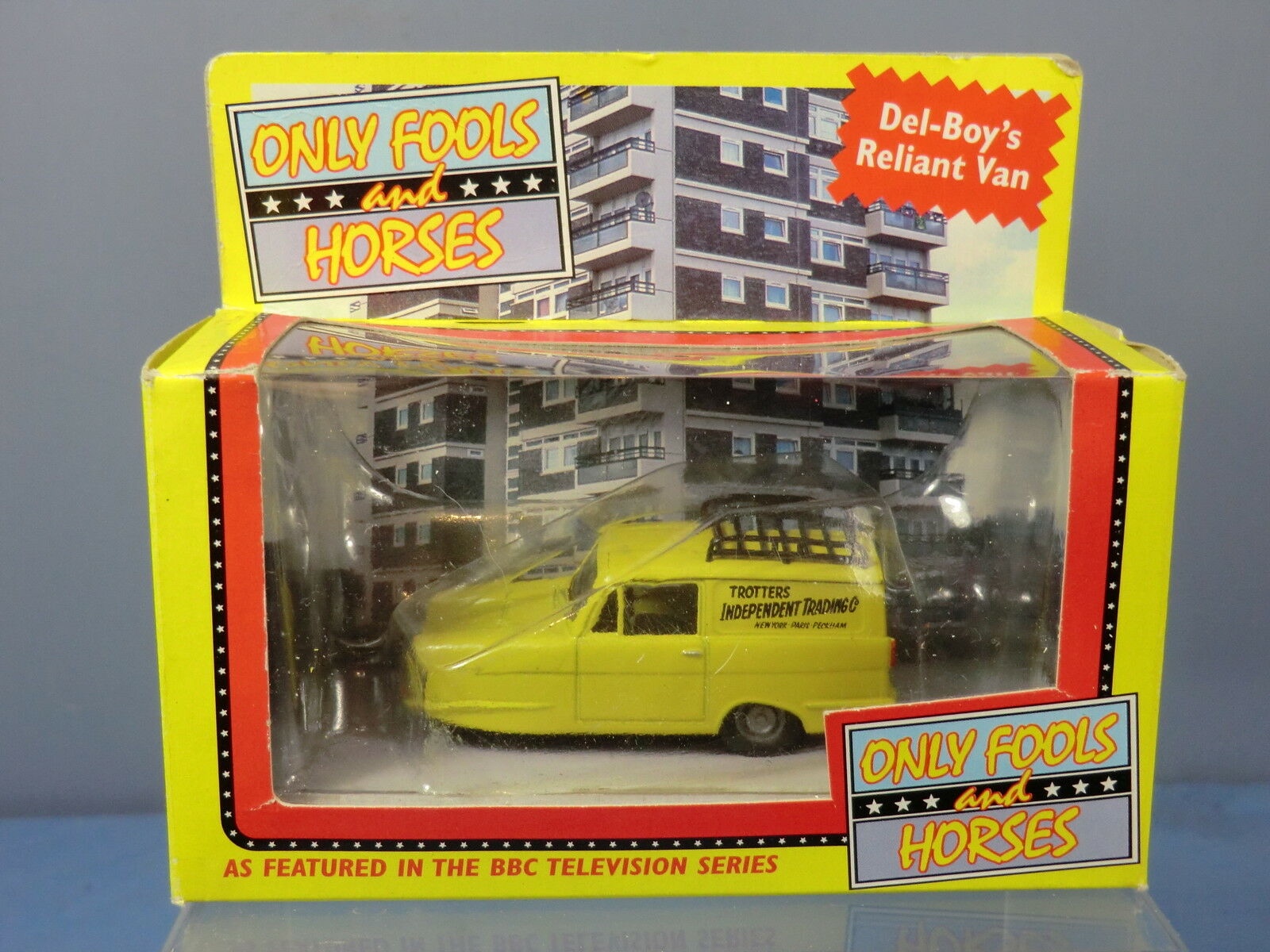

The Reliant Robin is a very well known car, but the majority of people have never driven one. The Reliant Motor Company made 3-wheeler vehicles from before the Second World War, originally as successors to Raleigh, who decided to pull out of that market. The series of passenger cars which led to the Robin began soon after the war with the Regal which was produced in various forms until the first Robin appeared in 1973. It was a Regal Supervan which appeared in 'Only Fools and Horses'. The Robin was essentially a rebodied Regal, although the chassis was new and the much more modern-looking car now rode on 10” Mini wheels in place of the 13” wheels used on the Regal. The engine was initially of 750cc and later 850cc, instead of the Regal's 700cc (earlier 600cc). The Robin was considered much more stable than the old Regal and capable of relatively high cornering speeds. It was eventually restyled to become the Rialto, before the Robin name was revived and the strange anachronism that the car had become continued to the turn of the century. It was killed off by a change in the law. Three-wheeled cars were not outlawed, but it became possible to drive a weight-restricted 4-wheeler 'microcar' on a motorcycle licence, leading to the import of such vehicles from France. The entire raison d'etre of the Reliant had long been that it enabled a full motorcycle licence-holder to drive a car-like vehicle (actually a motor-tricycle in law) without passing a driving test in a car. It remained particularly popular in areas such as South Yorkshire, where many housewives were condemned to a lifetime of being a passenger in a cramped, noisy and rough-riding 'plastic pig'. As the ageing clientele succumbed one-by-one to pneumocoliosis, sales were already dying away, but the Ligier and Microcar spelled the end. It is now a collector's item. Many were destroyed in banger races and there are relatively few working cars left. Prices for the best cars are in the £thousands. The Robin I owned in 2019 was sold to a classic car museum in Cyprus!

So much for the brief history. The main purpose of this article is not merely to give a pallid description of a bygone motoring oddity, but to bring it vividly to life as a challenging driving machine. Many will have seen Jeremy Clarkson repeatedly overturning in a Robin on the Top Gear programme. That 'car' had been 'doctored' to increase its instability, with a welded-up differential, differing rear wheel sizes and extra weight attached to the inside of the bodywork at the offside front corner, not to mention the not insignificant mass of Jeremy Clarkson himself, shifting the centre of gravity to the right-hand side of the 'car'. In reality the Robin could be driven safely in normal traffic conditions throughout a long life, as most were. However, the little 'car' did possess certain potentialities which meant that it certainly wasn't safe in the hands of an inexperienced or foolhardy driver. To understand this fully it is necessary that I explain what a Reliant Robin actually was. This may seem rather obvious to some of my readers, but not everyone knows what is under the glass reinforced plastic (GRP) skin. Every Reliant was built upon a steel chassis frame. From the mid-fifties the three-wheelers had GRP bodies. The engine was at the front and was a 4-cylinder pushrod four-stroke, driving through a 4-speed gearbox to the cart-spung rear axle, just like most cars of the 1950s and 60s. Where it differed was that a single, coil-sprung front wheel was immediately in front of the engine. Steering was by a steering box with a single steering arm. Drum brakes were fitted to all three wheels with the handbrake operating on the rear wheels. The engine was positioned between the legs of the driver and front passenger so that the footwells were extremely narrow, particularly so on the Robins, especially for the passenger. The front seats on the Robin in particular, were really tiny, as if designed for a small child. The rear bench seat was also small. The cabin was very narrow, such that full-sized people were wedged in together. The steeply raked screen of the Robin increased the claustrophobia. But this two hundred pound 5'11” driver did fit and wasn't too uncomfortable! The steering wheel was small and the stubby gearlever snicked briefly from ratio to ratio like a very mechanical switch. Delightful. Engine noise was ever present. If the 'tappets' were loose you would hear them. Set them correctly and you would still hear them. The engine was right next to you behind a thin wall of GRP and sound-deadening material. You could hear the gearbox too!

Driving this machine was motoring in its elemental form. You could hear the machinery at all times. You felt every irregularity of the road surface. The steering was very quick. The acceleration was surprisingly fierce from low speeds. You felt as if you were going twice as fast as you actually were. Sixty miles an hour in a Robin really did feel like a hundred and twenty in a proper car. At this point it is worth analysing the stability of the Robin. If you think about a three-legged stool, you'd have to admit that it is quite a stable seat, particularly if it is short. Three-legged stools don't wobble. As they get taller, so the stability becomes noticably worse than that of a comparable four-legged stool. Stools are stationary. The legs are equally spaced and you sit in the middle. The Robin had one 'leg' right at the front and the other two 'legs' rather close together towards the back. It also moved. You didn't sit in the middle. The all-alloy engine was near the front and low down in the comparatively heavy chassis. You and your passenger, should you have one, were relatively high-up and sitting rather on the edges of the 'stool', just ahead of the rear wheels. It is an important point that the Robin was such a light 'car' that the weight of the driver and passenger might increase the all-up weight of the 'car' to 50% above its kerb weight! They also raised the centre of gravity greatly. During acceleration in a straight line there was some rearward weight transfer. The 'car' remained stable. Under heavy braking in a straight line, there was forward weight transfer, but the 'car' still remained stable. Unfortunately, roads have corners and bends, although these features can provide some relief from the monotony of going in a straight line. When any car is driven around a bend centrifugal force acts upon it, such that it would roll if it could. The low centre of gravity and the widely spaced wheels resist the tendency, although the body of the car may lean towards the outside of the bend. Very stiff suspension or the use of anti-roll torsion bars will provide resistance to this. If the cornering speed is increased then the car may begin to slide as the grip of the tyres is overcome, at which point the driver might well reduce power to avoid sliding off the road or out of lane. If the grip of the tyres was infinite then roll-over would occur if the cornering speed was sufficient. Most drivers never explore such limits in modern cars.

In the case of the Reliant, the roll resistance was all at one end of the 'car'. There was no roll resistance at all at the front. If the centre of gravity was kept near to the rear of the 'car', the roll 'moment' about the front wheel would be fairly low and the higher roll 'moment' about the rear axle would be resisted by the rear springs and the reasonably widely-spaced rear wheels. All things being equal, the Robin would remain quite stable at relatively high cornering speeds, provided that the 'car' was accelerated through a bend, thus transferring some weight to the rear of the vehicle. Conversely, if the Robin was braked into a bend, transferring weight to the front of the 'car' where there was no roll resistance at all, the 'car' was much more likely to roll over. Initially, the front corner of the body would hit the road which might prevent the Robin rolling on to its side. The lifted rear wheel would also lose traction, slowing the 'car' down. So, all might not be lost! Adverse camber of the road could literally 'tip the balance', as could a strong crosswind!

In the last paragraph I used the phrase 'all things being equal'. With the driver only aboard all things were most definitely not equal. The heavier the driver, the greater the instability of the Robin on left-hand turns. The solo driver had to take much greater care on left-handers than right-handers. Driving technique needed to change to reflect the loading of the Robin. When driving solo I found that I could improve the balance of the 'car' by leaning across to the left during left-hand cornering. When accelerating through a bend, if the speed was sufficient, it was still possible that the 'car' would begin to lift an inside rear wheel. However, as the wheel began to lift, traction was lost and the Robin slowed down, thus restoring the status quo ante. You could call it 'traction control'. On a smooth surface therefore, it was impossible to actually roll the Robin by accelerating too much through the corner. Entering a corner at too high a speed was a different matter and woe betide you if you then braked! On the subject of stability, one last point. Because the Robin has only three wheels, when a rear wheel hits a bump there is not a diagonally opposite front wheel to resist the bouncing of that corner of the vehicle. As a result, when the 'car' was at the limit of its roll stability, striking a sizeable bump with the inside rear wheel would easily push it 'over the edge', the wheel being so lightly loaded that the leaf spring would not absorb the shock. All of the above may suggest to you that anyone travelling in a Robin was taking 'their life in their hands' but in real life these vehicles had a good accident record and were inexpensive to insure. Statistically you were less likely to be in an accident in a Robin than in a Ford Mondeo. Despite the relative instability and appalling crashworthiness of the little Reliant, relatively few people were ever killed in it. In addition to the Robin I had in 2019, I've owned two of the less stable Regals, which I drove no less enterprisingly. In those 'cars', with their inferior crossply tyres, I actually found it possible to slide the rear wheels and use opposite lock! The nearest I got to rolling one was when taking a very tight left turn with an adverse camber, being part way down a steep hill. I was doing about 7 mph and remained perfectly balanced on two wheels for about five yards.

In conclusion, the Reliant three-wheeler was a minimalistic, crude and archaic design which changed very little technologically after 1962. Keeping the weight below the 8cwt and later 400kg limit resulted in some of its more primitive aspects. It was very economical and, with the later galvanised chassis, remarkably durable. It was also one of the most challenging, involving and exciting vehicles I have ever driven and one in which I frightened a good friend more than in any other, including a Triumph Spitfire powered by a tuned Rover V8. The fact is that a well-driven Robin can be cornered faster than most people would believe possible, yet the sense of impending disaster for the passenger is akin to that of a traveller in a Boeing 737 Max, without the upgrades.