the curious case of the morris cowley

The Series 2 Oxford's plain sister.

By: Terry Burgess Thu, 30 Apr 2020

Features

William Morris, later to become Lord Nuffield, was a little short of imagination when it came to finding names for his cars. I suppose it is some credit to him that he gave them names at all, at a time when most other UK manufacturers simply gave their models numbers, such as 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18 and 20 representing their RAC horsepower ratings, which had nothing to do with the actual power of the engine and gave only a clue as to the cubic capacity. It was a formula used for taxation purposes which took account of the cylinder bore dimension and the number of cylinders, but strangely ignored the stroke thus encouraging manufacturers to produce small bore, long stroke engines to achieve the largest possible engine capacity with the lowest road tax rating. These engines produced good torque but the resultant high piston speeds meant that they suffered from premature piston and big end bearing wear and were intolerant of high-speed cruising, rendering them unsuitable for export to countries with fast trunk routes, a situation which would remain unchanged until after World War 2 when a flat-rate taxation system was introduced and large bore engines rapidly appeared.

I digress. William Morris, who produced his rather good motor cars in a university town about 40 miles west of the capital, hit upon the brilliant idea of naming his car after the town in which it was built, hence the Morris Oxford! On the next occasion when he required inspiration for a new model name he needed to look no further than the suburb in which his cars were built, namely Cowley! Had he looked a little further afield we might have had a Morris Toot Baldon or a Morris Charlton-on-Otmoor, but he didn't so hard luck.

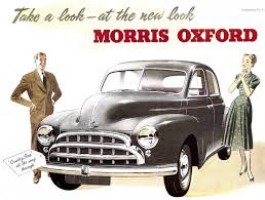

The cars to which I refer became the famous Bull-nose Morrises although flat-nosed versions were later produced. These venerable cars are not the subject of this article. After WWII, in 1948, three new Morris cars were announced, the Minor (MM), the Oxford (MO) and the Six (MS) and all were designed by Alec Issigonis. The Oxford name had been dropped from the Morris catalogue in 1935 to be replaced by 'names' such 'Eighteen' and 'Twenty'(!), although it had been revived for the Nuffield Oxford Taxi from 1947. The three new cars shared generally similar styling but the MM and MO used 4-cylinder sidevalve engines whereas the MS used an SOHC straight six. The smaller cars gave a very modest performance but handled well with their torsion-bar independent front suspension and rack and pinion steering and were very successful models. The Oxford continued in production until 1954, by which time the Nuffield Organisation had merged with the Austin Motor Company to form the British Motor Corporation. Although described as a merger, this was essentially a takeover by Austin, now under the leadership of none other than Leonard Lord who had left Morris in 1938 with the reported declaration, “I'll be back and I'll take this place apart brick by bloody brick!”

Oxford MO

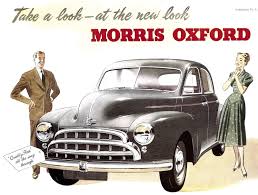

Meanwhile, Alec Issigonis had left Morris in 1952 to join Alvis, but not before designing a replacement for the Oxford MO, namely the car which became the Oxford Series 2, and which, by the time it entered production in mid-1954, had been fitted with an Austin-designed 1489cc B-series engine driving through a corporate BMC 4-speed column-change gearbox and BMC rear axle, the fruits of BMC rationalisation.

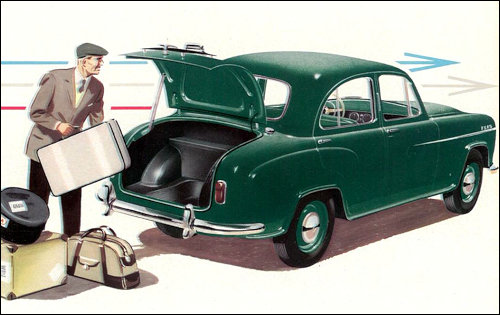

The fact that Issigonis had designed the car was evident from the continued use of torsion bar front suspension and rack and pinion steering (unlike the Austins with their double wishbones, coil springs and steering boxes), but even more so from the remarkable space utilisation achieved on the new Morris. It was considered a rather plain design by the press, with a shortish bonnet, bulbous boot and remarkably large windows for the time. Function rather than form. Anyone familiar with the later BMC Mini would recognise elements of its design in the Series 2 Oxford. The shape of the front end is actually very similar as is the design of the 'dashboard', having top and bottom rails and centrally mounted instruments, with open shelf space either side. Even the rather flat angle of the steering wheel seems familiar, although in the Oxford it was also tilted towards the driver's door to increase the car's utility as a full six-seater. The sense of spaciousness in the Oxford was terrific for the compact size of the car, just as it was in the Mini. The floor was near to being flat and there was plenty of legroom for rear-seat passengers. The internal width of the car was increased by the use of thin vertical doors and side windows and the seats occupied all of the available width. No BMC family car until the advent of the Austin 1800 was so space efficient. Recognising this and the car's excellent road manners due to its relatively advanced steering and suspension is the key to understanding the brilliance of the design. What appears to be 'grey porridge' was actually, for its time, a great car.

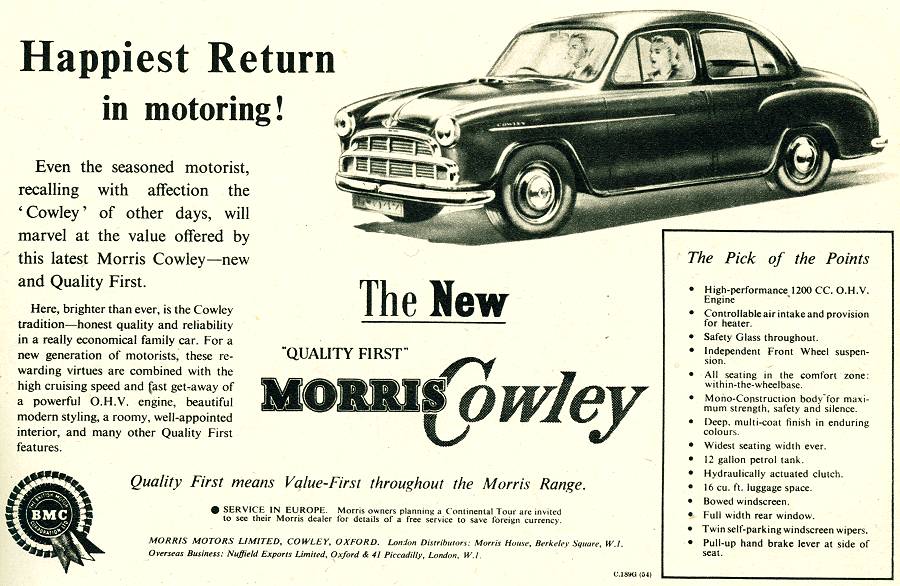

Two months after the introduction of the new Oxford came the new Cowley. Pre-war Cowleys were family cars and so was the new one. Enthusiasts were somewhat disappointed to discover that this was just a stripped out, lower-powered and cheaper version of the new Oxford. It is believed that the only reason for its existence was that the parallel Austin and Morris distribution networks must be provided with competing models at all levels and Austin had the new A40 Cambridge with the '1200' engine, therefore the Morris dealers must have a '1200' of their own to sell. The motoring press duly reported on the 'new' model and found that it was a truly adequate family car for the man 'not in a hurry' although the performance was actually regarded as very satisfactory, being superior to that of the old Oxford MO, and fuel economy, if the car was driven slowly, could be very good. The difference in price between the Cowley and the Oxford was £42 10s 0d including purchase tax, £702 0s 0d vs. £744 10s 0d. For the extra money the Oxford buyer got a fresh air heater, carpets in place of felt mats, leather upholstery, a 1489cc rather than 1198cc engine, four bumper overriders, an extra sunvisor, a clock, a temperature gauge, a horn ring, more elaborate door cards, and extra chrome embellishment to the the body sides and grille. In normal motoring the fuel economy was almost the same on each car and the Cowley suffered the indignity of lower overall gearing to compensate for the loss of no less than 20lb/ft of engine torque.

In excess of 17,000 Cowleys were sold in 2 years, compared with 80,000 Series 2 Oxfords. The wonder of it is that anyone bought the Cowley at all for such a meagre saving. It made the Oxford look like the bargain of the decade.

Oxford Series 2

A Series 3 Oxford was introduced in late 1956, alongside a Cowley '1500', having significant styling changes to the rear, a 'fluted' bonnet lid and a new dashboard with a padded top and gloveboxes. Issigonis' purity of design was lost in an attempt to 'keep up with the times'. Both the Series 2 and Series 3 Oxfords were produced in India under licence as the Hindustan Landmaster and Ambassador and the latter remained in production in modified form until 2014, keeping the type alive in the minds of UK enthusiasts, long after the originals had vanished from the roads of Britain. I have studied film clips of London street and traffic scenes of the mid and late 1960s. The 1950s Oxfords and Cowleys are nowhere to be seen, unlike their Austin counterparts which appear here and there, even the old A40 Somersets. The Austins were built in greater numbers, but not sufficiently so as to account for the difference. By the 1970s, when I was buying old cars, the mid-fifties' larger Morris cars were not to be found, whereas there were, unsurprisingly in view of the huge numbers built, plenty of old Minors and I even managed to buy a 1951 A70 Hereford from a newsagent's noticeboard. As a car fanatic, I was aware of the old Cowleys and Oxfords but they were not objects of desire for me at that time.

You may be wondering why so few of these worthy cars remained by the end of the 1960s. The answer is underneath the car. The Oxford or Cowley rusted away just like all British family cars of the time but, due to specific design features which were quite different from its main competitors, the corrosion more quickly rendered the car incapable of passing an MOT test without major repairs. Most medium sized family cars of the time had strong box-section members running all the way from the front to the rear of the floorpan. At the front would be a bolt-on crossmember to which would be attached the front suspension and the leaf-type rear springs would attach to the rear of this vestigial chassis. Corrosion in the outer extremities of the welded-in crossmembers or the inner and outer body sills was not considered important in those pre-seatbelt era cars. The Cowley and Oxford however, had 'chassis' longerons only as far back as the crossmember to which the front suspension torsion bars were attached. Thereafter the strength of the box-section sills was essential. Corrosion in those or in the vital crossmember would therefore condemn the car. At that time professional repairs to the bodyshell would have been relatively expensive using oxy-acetylene equipment and suitable electric welding equipment for home use was some time in the future. Resultantly these increasingly unfashionable cars were almost all scrapped long before they would be regarded as 'classic'.

About 18 years ago I saw a green Cowley '1200' advertised on a supermarket noticeboard for £1500. It was described as being in a restored condition. I knew well enough what it was and I remember saying that it was an awful lot of money for such an undesirable car. I couldn't think of a single reason why I should want it.

Eighteen months ago I bought a Clarendon grey 1955 Cowley for a greater sum in unrestored condition, although with a low mileage of 62500 and its original engine. I attempted to drive it home but due to a problem with the clutch release mechanism it arrived very late on the back of a recovery truck. It would be some time before the car was ready to drive.

Series 3 Oxford

Today I still have it. I have a keen eye for its virtues, some of which I have already mentioned. The Cowley is far less common than the Oxford, though both could be described as 'rare'. The PVC upholstery is in much better condition than would be the leather of an Oxford after 65 years. The '1200' engine has a certain cachet in being the smallest capacity true B-series ever produced. It is not the same engine as the '1200' fitted to the A40 Devon and Somerset models which were physically smaller pre b-series units. Curiously, the smallest B-series engine is always referred to as being of 1200cc capacity, even in the official workshop manual and driver's handbook, whereas the larger 1489cc, 1622cc and 1798cc B-series units are generally quoted as such, correct to the nearest cubic centimetre. In fact the '1200' is of 1198cc capacity, but nowhere have I ever seen that figure in print for that engine.

It has only 42bhp and 58lb/ft of torque, rather meagre for a car weighing over a ton unladen, but it gets along very nicely without the need for straining the engine. It is an extremely smooth performer, having smaller, lighter pistons and a low, 7.2:1 compression ratio, but the same strong crankshaft and bearings as the other B-series engines right up to the 1798cc 95bhp 3-bearing unit fitted to the earliest MGBs, so the bottom end has an easy time of it, as does the transmission. As a 65 year-old classic car it really does have a great deal to recommend it, and strangely enough I also find the Cowley to be a thing of beauty. I stand and admire it's perfection. It is a joy to purr along at 40-45mph on a country lane with a decent enough ride and positive steering. The long-throw column gearchange is a pleasure to use. The old car makes lovely noises too, and 35mpg shouldn't be that hard to achieve. It will cruise along very well at 50-55mph which isn't so great an irritation to other road users I hope. It is delightful to experience motoring as it was in the mid-fifties without the benefits of 'sympathetic upgrades' to the specification.

I've always had a thing about largish cars with small engines.

Curious isn't it?

Footnotes

Oldclassiccar.co.uk