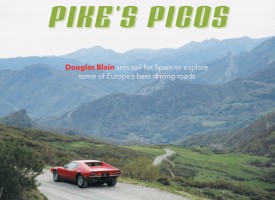

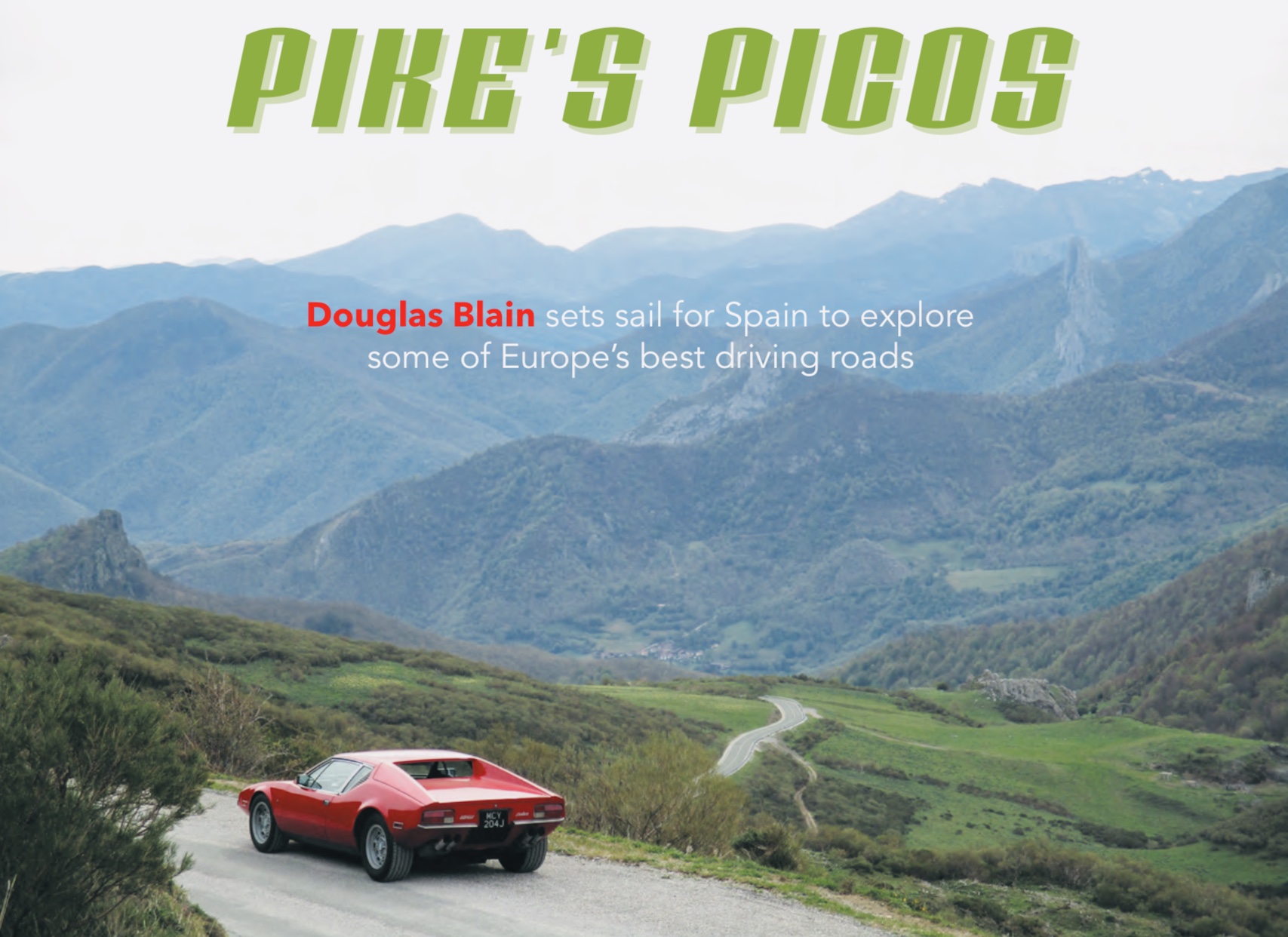

pike’s picos de tomaso pantera

Douglas Blain sets sail for Spain to explore

By: Douglas Blaine Fri, 01 Sep 2017

Features

Call it cultural deprivation, or maybe just accident, but Spain has figured far too little in my life so far. The Costas were never going to be my thing, and Spanish as a language eluded me at school. Then, when motoring became a passion and, for a time, a livelihood, the glory days of Hispano-Suiza and Pegaso were long gone. So, apart from one unforgettable trek by prototype Range Rover through Don Quixote country with dear old Steady Barker, followed years later by a cultural family pilgrimage to the Napoleonic battlefields of the Extremadura, there has been lamentably little to feed the fading memory bank compared to what has accumulated from France and Italy.

Until this Spring. That was when a random mailing from Brittany Ferries alerted me to the benefits of combining what they call a discounted off-season return ‘cruise’ between Portsmouth or Plymouth and Santander or Bilbao with very reasonably priced half-board accommodation in one’s choice of parador. This meshed perfectly with a plan my co- owner Tim Jackson-Stops and I had been hatching to give our newly refreshed de Tomaso Pantera a shakedown on deserted and suitably challenging roads, rather in the manner of the traverse of Australia’s Great Ocean Road I wrote about in the March issue. Unlike the 1922 Ballot 2LS we did that trip in, the Pantera (ours was built in 1971) is slightly outside The Automobile’s current comfort zone and therefore not the point of this story. What is very much to the point is the particular patch of northern Spain we chose for our adventure, incorporating as it does what I can now recommend as some of the best driving country in the whole of Europe. Covering an area of some 250 square miles and located so accessibly only just to the south- west of Santander, the Picos de Europa National Park is a range of rocky, virtually treeless peaks soaring like sharks’ teeth straight out of the surrounding plains to a height of almost 8000 feet – much taller, in other words, than anything in the UK, more rugged than even the most remote bits of Scotland and, unlike the Alps, the Dolomites or other mountain ranges given over to tourism, innocent of development of any kind. Result: no traffic. Consequence: motoring heaven. Our overnight outward voyage was from Plymouth, as it happened, and the notorious Bay of Biscay was benign. The good ship Port Aven turned out to be, as advertised, more compact cruiser than ferry, with proper scrubbed decks, even a swimming pool, plus an excellent restaurant with pretty Bretonne waitresses and good wine. Knowing one is not going to be turfed out of bed at 5:30am takes some beating as a sleeping pill, so we docked refreshed and ready for action in the early afternoon.

Our destination that first day was Fuente Dé, a tiny hamlet at the end of a long, rocky rift in the Picos. The place is a favourite, naturally, with walkers and climbers of the braver sort, and for the rest of us there is Europe’s longest single-span cable car right outside the hotel’s back door.

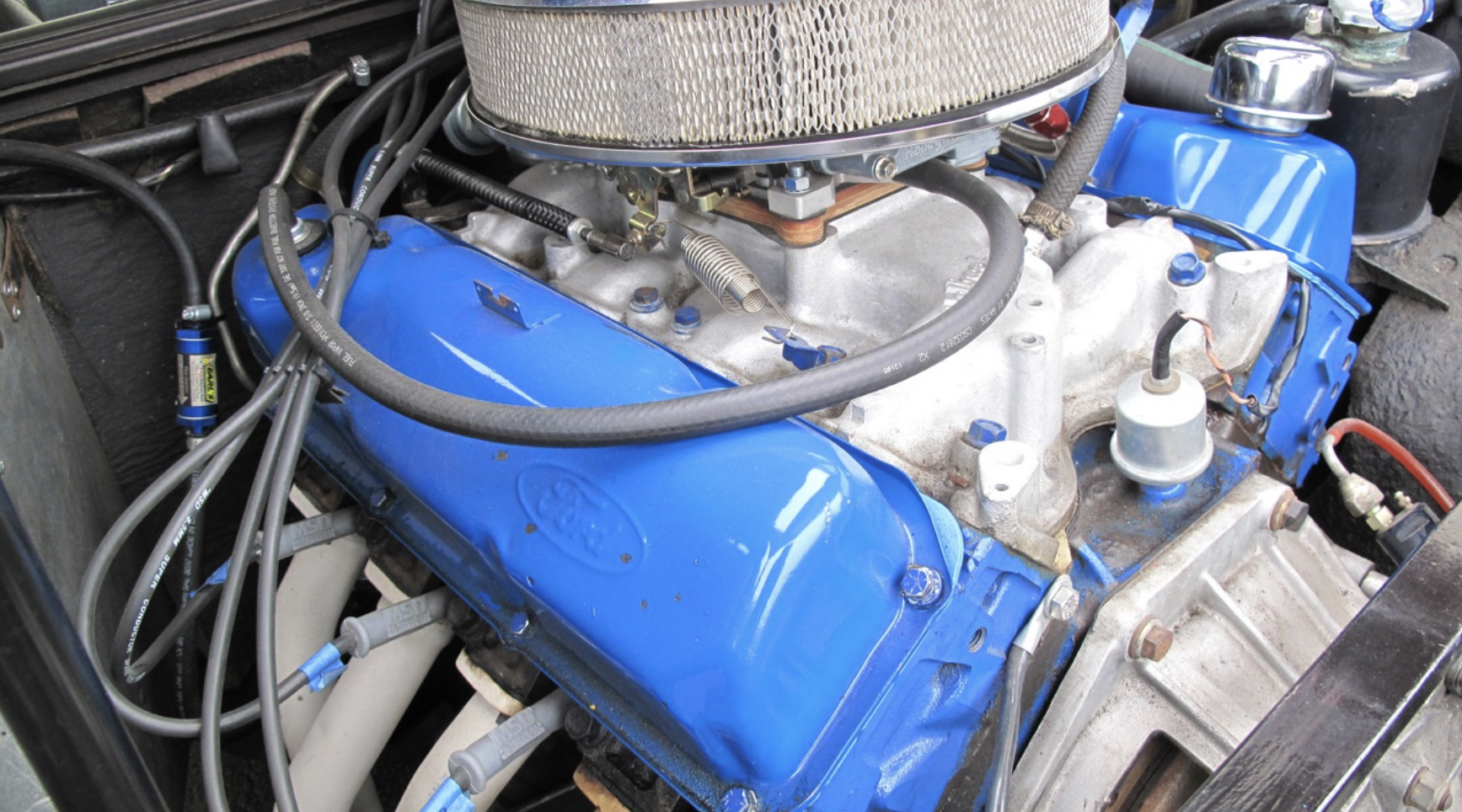

To get there, Tim, an experienced navigator in HRGs and E-types, chose a sequence of switchback mountain roads which put the Pantera on full alert. Six litres of mid-mounted Ford Cleveland V8 give this compact pre-L two-seater almost unlimited grunt, transmitted to the back wheels (fatter than the front ones, a novelty at the time) via a fine five-speed ZF transaxle with aptly long ratios and a limited-slip differential. Although the car was marketed in period as a Miura for the price of a Mustang, and my old friend Gianpaolo Dallara succeeded in giving it the same performance up to 100mph or so as his Lamborghini, but the Miura, as I remember writing at the time, was a gloriously selfish, dangerous, pollution- ridden status symbol that none of us who drove it will ever forget – ‘the 20th century equivalent of the duelling pistols, thigh boots, cocked hat, swordstick and other virility symbols of a bygone age’. Driving the Pantera hard is a very different experience. Instead of playing tunes on the gearbox and maxing revs in the lower ratios just for the hell of it, with so much low-speed torque on tap one tends to hold third or even fourth, keeping second for the vertical bits and rarely needing first. One’s concentration is on reading the road (even the remotest ones here tend to be well engineered, and pothole- as well as traffic-free), getting braking out of the way early and nailing the torque curve with precision as one clips each apex.

For those unfamiliar with the phenomenon, a parador is a hotel owned and run by the Spanish state to a standard which, though uniformly high, is some way short of today’s six-star aspirations. The idea originated in the 1920s and was developed strongly after the Civil War by the dictator General Franco, who found himself with a worthless currency and a plethora of empty castles, palaces, religious institutions and other historic buildings that cash-rich foreigners might enjoy spending time in. Checking out of this one after a hearty breakfast and heading north, we soon found ourselves in the neighbouring Sierra de Alba mountain range: less steep, more open, with the occasional long straight stretch offering the ideal opportunity to assess the Pantera as a high-speed, long-distance mile-eater. We were heading for the cathedral city of Léon, on the time-worn route to Santiago de Compostela, and already there were groups of scallop shell-badged pilgrims to be seen plodding along the dusty verges, springtime harbingers of the 300,000 who do the trek each year. They, and the odd herd of similarly long- haired mountain sheep, the latter kept in check by murderous-looking mastiffs, were our only fellow travellers until we reached the main 601 trunk road into the city itself. Suitably uplifted by the breathtaking array of stained glass in the 13th century cathedral’s soaring clerestory, we pressed on towards our second night stop, Corbera de Pisuerga, a parador built, like the previous one, in the 1960s in traditional style on a lonely site high in yet another mountain range, the Sierra de Peña Labra. En route we found ourselves in rich, rolling, lightly wooded country which soon gave way to some of the most testing hairpins we were to encounter: rougher, less predictable switchbacks with hard masonry parapets lying in wait. At one point I found it impossible to avoid a fallen rock which proved just a fraction fatter than the Pantera’s reasonably generous ground clearance, but luckily the stout box- section rear subframe turned out to have been the only point of contact. In a Miura, one reflected ruefully, it would have been the cast alloy sump. The conditions reminded me irresistibly of Piedmont in the 1960s and early ’70s, where I would take a new car like the Pantera out for the day from Turin at showtime and exercise it vigorously in the hilly wine country around Barolo. That was in the days before speed limits and cameras, of course, and in remote rural Spain for the most part we are still very much back there. Only on motorways did we notice cameras, all of them flagged, as in France, by prominent signage, and never once during our spirited travels on country roads did we spot a police patrol. For us, that suggested a routine involving dutiful observance of signposted limits in towns and villages with vigorous bouts of acceleration and fast cruising in between – precisely what supercars of 40-odd years ago were built for, rather than being blasted noisily up and down the King’s Road by 17-year-old Middle Eastern princelings as is their fate today.

Top speed? Road tests back in the day suggested 160mph was achievable. I never got quite that far in a test Pantera, and on this occasion we contented ourselves with the odd burst to 120 or even 130 when conditions felt right. At those speeds the car turned out to be rock steady, impervious to side winds and by no means noisy. There was clearly more to come, but we had nothing to prove. As a result of this restraint, our fuel consumption was running at 25mpg or so in all but the mountainous hinterland, when it dropped to 20 rather than the eight, 12 or 14 I remember getting from the model’s multi-cylinder competitors back then. A thunderstorm that had hovered all afternoon caught up with us that evening as we sat on the hotel terrace overlooking a vast mountain landscape with vultures wheeling, motionless, overhead. It was dry again by morning as we set off for Burgos, our second cathedral city of the tour, pausing on the way at Villadiego, a tiny, partly fortified early town that had, as we learned from prominent posters on the outskirts, benefitted from a recent World Monument Fund grant. The shady marketplace, lined with 16th century buildings in which tiers of oriel windows balanced shakily on top of stone and timber columns, their chimneys bristling with storks’ nests, proved ideal for a reviving glass each of the local ale while we listened to the ancient town hall clock go through its cacophonous, out-of-tune routine. On now through hilly rather than mountainous terrain to Burgos – more pilgrims, more mediaeval marvels, more yummy tapas – and then to our last overnight stop, yet another cathedral environment, that of San Domingo de la Calzada. Much less well known, and very much smaller, this is a destination with an irresistible story to tell. St Domingo was a humble 11th century hermit who, taking pity on the Santiago pilgrims of his day, built them a sanctuary in which to rest and offered them what medical care he could. By the 14th century the sanctuary, administered by generations of his followers, had become a magnificent vaulted stone hospital which, now redundant, forms the core of the parador we stayed in. As for Domingo’s primitive wooden church, it is today a fine cathedral with a free- standing Classical tower and, by Papal dispensation dated 1350, a Gothic coop, no less, in the wall housing a live cock and hen. As so often in Spain, one is free to wander up secret staircases and along intramural passages built into the edifice, peering down through squints and spyholes and occasionally emerging onto the leaded roofs. It was from here that we spotted a festival dedicated (one of many) to the holy man himself in full swing in the streets below, with groups of what we would call Morris dancers swinging round the precious car we had left casually parked in the square and a neatly dressed six-year-old seated, grinning broadly, behind the wheel. In due deference to St Domingo, we let her take her time. The last day had been set aside for Gehry’s sensational Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, so we took the motorway there to save time. We had covered some 650 miles on a lozenge-shaped route in three days, enjoyed some extraordinary experiences, explored the limits of our Pantera’s capabilities and reinforced our affection for a nation and its people who, emerging only now from a rough patch economically, never fail to charm with their helpfulness and hospitality.

D E B

Footnotes

Travel note: Douglas’s share of the cost of this off-season five-day Brittany Ferries package, brilliantly organised for us by Caroline Paymayesh here in the office, including half the shipping charge for the car, a single cabin each both ways and three nights in paradores with his own room and half-board, came to £579. For two people sharing, this figure would come down to £440 – cheaper, almost, than a rubbish package on the Costa del Crime.

The Automobile magazine September 2017